Data Execution Prevention

And how attackers can bypass DEP to achieve code execution.

Hey, y’all! Welcome back to the binary exploitation series. So far, we’ve delved into some exploitation techniques such as buffer overflow, buffer overread, and format string attacks.

Today, we are going to take a look at one of the security features commonly built into operating systems that are meant to mitigate these attacks, and how they can be bypassed.

Data Execution Prevention (DEP)

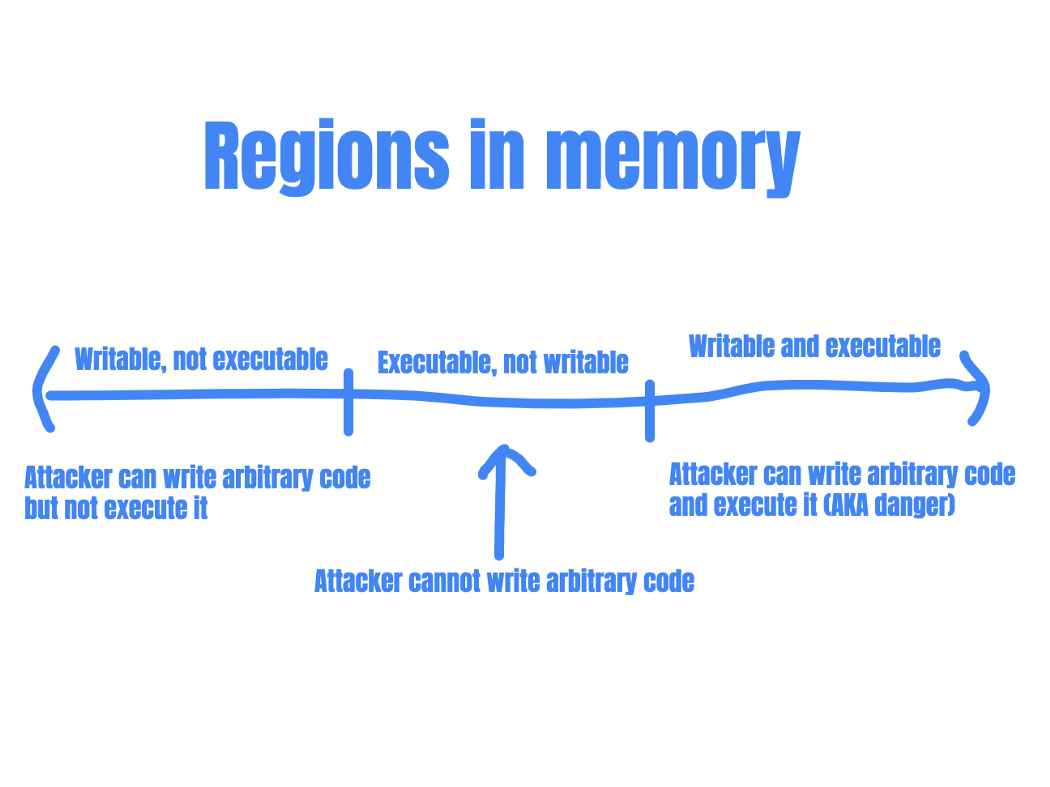

As mention in previous articles, memory corruption bugs can lead to attackers injecting and executing their own code. These attacks rely on parts of the memory being both writable and executable. (So that the attacker can write their code into the memory region, and subsequently execute that code.) If there are no memory regions that satisfy these two conditions, this type of attack would fail.

Protecting the system by rejecting code execution

Thus, data execution prevention was introduced. DEP marks certain areas in memory (typically the user-writable parts) as non-executable so that attempts to execute code in these regions would cause an exception.

This is a very useful protection technique as it essentially prevents attackers from executing injected shellcode. (In the context of binary exploitation, shellcode refers to instructions that are injected and then executed by attackers.)

However, a system with DEP implemented is not hacker-proof. A technique that is commonly used to bypass the limitations set forth by DEP is Return Oriented Programming (ROP).

Return Oriented Programming

Return Oriented Programming is an exploit technique that allows attackers to execute code regardless of DEP.

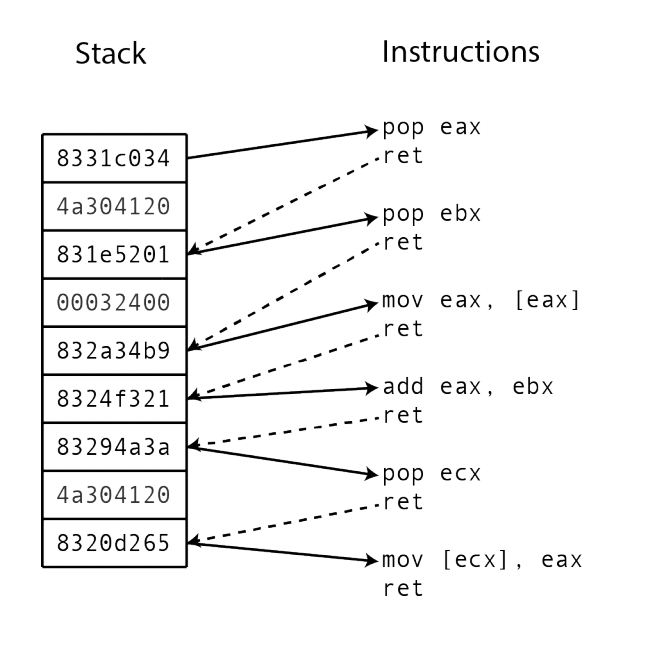

In ROP, the entry point of the attack is still some form of memory corruption: the attacker would need a way to hijack the program control flow. The attacker can then continue to redirect the program flow to use snippets of code already in the codebase (called “gadgets”). Chaining these gadgets together, the attacker can pretty much replicate the effects of custom shellcode.

Each gadget executes a small part of the computation desired by the attacker, such as adding to a register or writing it into a register.

Gadgets typically end in a “return” instruction. This allows attackers to return the program flow to the stack. The attacker can then redirect program flow to the next gadget.

Attacker redirects program to gadget location

-> gadget code performs small action

-> returns to stack

-> attacker redirects program to another gadget

-> gadget performs small action

-> returns to stack ... and so on

And this is why ROP works: the attacker is not writing any executable code into memory, just reusing code that is already being used by the program! DEP makes exploitation harder, as gadgets take time to find and chain, but it is almost always possible to achieve the same results as custom shellcode.

Overcoming Limitations of ROP: Stack Pivoting

However, after finding a memory corruption bug, it is not always possible to place a complete ROP chain on the stack like in the above image. Sometimes an attacker is only able to overwrite a single address on the stack. Does this mean that the ROP chain is no longer possible?

In this case, attackers can utilize a technique called a “stack pivot”. During a stack pivot attack, the attacker uses the one gadget that she can control to move the stack pointer to a different location.

For example, the attacker can create a fake stack at a location that she can write to, and store the ROP chain there (place the list of addresses of gadgets there). Then, she can utilize the overwrite on the real stack to point to a gadget that moves the stack pointer to the fake stack, kick-starting the ROP chain.

Attacker can only overwrite a single address on stack

-> attacker places the ROP chain on heap (fake stack)

-> attacker uses one gadget to point stack pointer to fake stack

-> ROP chain starts at fake stack

Ret2libc attacks

Ret2libc is another technique that attackers can use to bypass DEP.

Ret2libc stands for “return to libc”, where libc refers to the C standard library. In a ret2libc attack, the attacker redirects the program flow to functions in the C standard library. Common targets include system(), open(), read(), write() and so on. These functions are almost always available to attackers and can provide a lot of value in practical exploitation.

Instead of placing custom shellcode in memory or finding and chaining gadgets, attackers can simply make use of functions already being used by the program.

For example, the C code system(“/bin/sh”) can be used to spawn an interactive shell. This is essentially a call to the C system() function with a single argument ”/bin/sh”. This means that if the attacker can place the argument ”/bin/sh” on the stack, and redirect program flow to the address of system() using a memory corruption technique, she can get arbitrary code execution.

The anatomy of the attack becomes like this:

Attacker has limited overwrite on stack

-> The stack is non-executable, cannot use custom shellcode

-> Attacker place the address of system() on stack

-> Attacker places "/bin/sh" on stack as an argument for system()

-> System executes system("/bin/sh")

-> An interactive shell is spawned

Thanks for reading! In this post, we went over what DEP is and how attackers might bypass it. Next time, we’ll dive into other methods of protection against binary exploitation, and some example exploits in detail.