Protecting Binaries

How modern binaries protect against attacks and how these protections are bypassed.

There are three main techniques used to mitigate binary exploitation in modern programs: Data Execution Prevention (DEP), Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) and Stack Canaries.

Together, these techniques make exploitation much more difficult for attackers when exploitable bugs (such as buffer overflows) are found. However, these protection techniques are not undefeatable. And attackers have found creative ways to bypass the constraints of these methods.

Today, let’s dive into the techniques used to protect modern binaries and how attackers can potentially bypass them.

Protection 1: Data Execution Prevention (DEP)

We’ve delved into some exploitation techniques such as buffer overflow, buffer overread, and format string attacks. These memory corruption bugs can lead to attackers injecting and executing their own code.

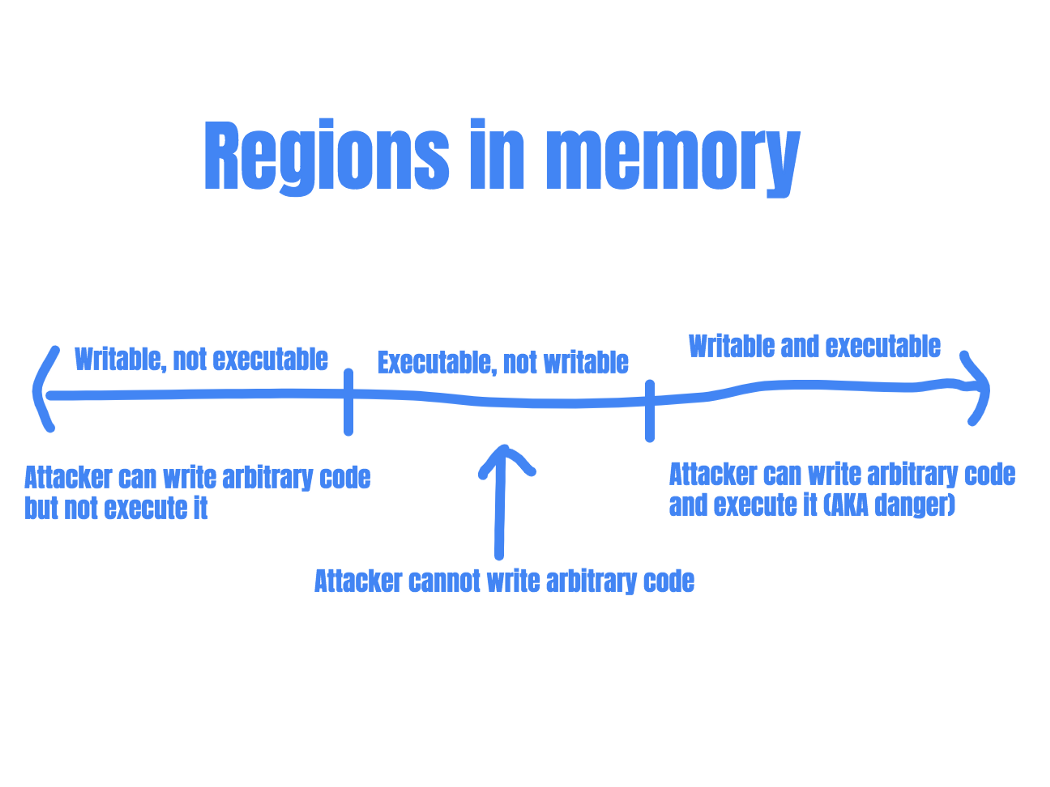

These attacks rely on parts of the memory being both writable and executable. (So that the attacker can write their code into the memory region, and subsequently execute that code.) If there are no memory regions that satisfy these two conditions, this type of attack would fail.

Protecting the system by rejecting code execution

Thus, data execution prevention was introduced. DEP marks certain areas in memory (typically the user-writable parts) as non-executable so that attempts to execute code in these regions would cause an exception.

This is a very useful protection technique as it essentially prevents attackers from executing injected shellcode. (In the context of binary exploitation, shellcode refers to instructions that are injected and then executed by attackers.)

However, a system with DEP implemented is not hacker-proof. A technique that is commonly used to bypass the limitations set forth by DEP is Return Oriented Programming (ROP).

Protection Bypass: Return Oriented Programming

Return Oriented Programming is an exploit technique that allows attackers to execute code regardless of DEP.

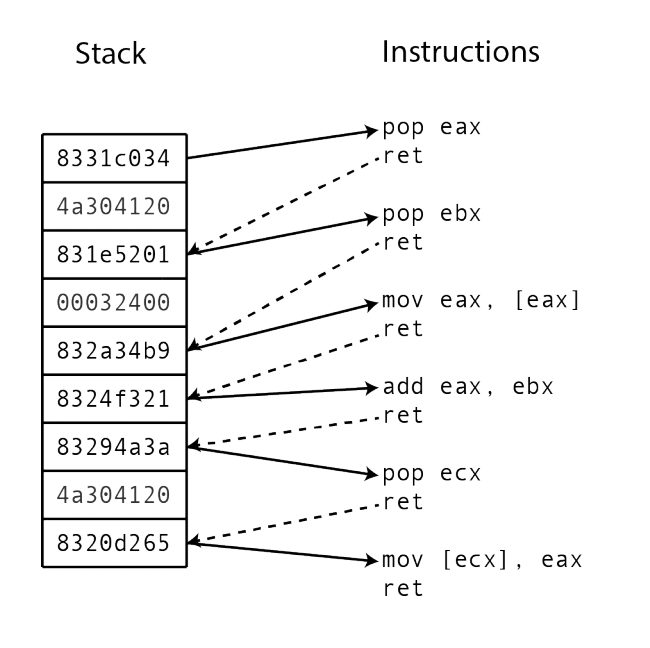

In ROP, the entry point of the attack is still some form of memory corruption: the attacker would need a way to hijack the program control flow. The attacker can then continue to redirect the program flow to use snippets of code already in the codebase (called “gadgets”). Chaining these gadgets together, the attacker can pretty much replicate the effects of custom shellcode.

Each gadget executes a small part of the computation desired by the attacker, such as adding to a register or writing it into a register.

Gadgets typically end in a “return” instruction. This allows attackers to return the program flow to the stack. The attacker can then redirect program flow to the next gadget.

Attacker redirects program to gadget location

-> gadget code performs small action

-> returns to stack

-> attacker redirects program to another gadget

-> gadget performs small action

-> returns to stack ... and so on

And this is why ROP works: the attacker is not writing any executable code into memory, just reusing code that is already being used by the program! DEP makes exploitation harder, as gadgets take time to find and chain, but it is almost always possible to achieve the same results as custom shellcode.

Stack Pivoting

However, after finding a memory corruption bug, it is not always possible to place a complete ROP chain on the stack like in the above image. Sometimes an attacker is only able to overwrite a single address on the stack. Does this mean that the ROP chain is no longer possible?

In this case, attackers can utilize a technique called a “stack pivot”. During a stack pivot attack, the attacker uses the one gadget that she can control to move the stack pointer to a different location.

For example, the attacker can create a fake stack at a location that she can write to, and store the ROP chain there (place the list of addresses of gadgets there). Then, she can utilize the overwrite on the real stack to point to a gadget that moves the stack pointer to the fake stack, kick-starting the ROP chain.

Attacker can only overwrite a single address on stack

-> attacker places the ROP chain on heap (fake stack)

-> attacker uses one gadget to point stack pointer to fake stack

-> ROP chain starts at fake stack

Protection Bypass: Ret2libc attacks

Ret2libc is another technique that attackers can use to bypass DEP.

Ret2libc stands for “return to libc”, where libc refers to the C standard library. In a ret2libc attack, the attacker redirects the program flow to functions in the C standard library. Common targets include system(), open(), read(), write() and so on. These functions are almost always available to attackers and can provide a lot of value in practical exploitation.

Instead of placing custom shellcode in memory or finding and chaining gadgets, attackers can simply make use of functions already being used by the program.

For example, the C code system(“/bin/sh”) can be used to spawn an interactive shell. This is essentially a call to the C system() function with a single argument ”/bin/sh”. This means that if the attacker can place the argument ”/bin/sh” on the stack, and redirect program flow to the address of system() using a memory corruption technique, she can get arbitrary code execution.

The anatomy of the attack becomes like this:

Attacker has limited overwrite on stack

-> The stack is non-executable, cannot use custom shellcode

-> Attacker place the address of system() on stack

-> Attacker places "/bin/sh" on stack as an argument for system()

-> System executes system("/bin/sh")

-> An interactive shell is spawned

Protection 2: Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)

Protection bypass techniques like ROP and Ret2libc means that DEP by itself is not enough to prevent hackers from building exploits. This is why the Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) is used.

Protecting the system by randomizing addresses of important memory segments

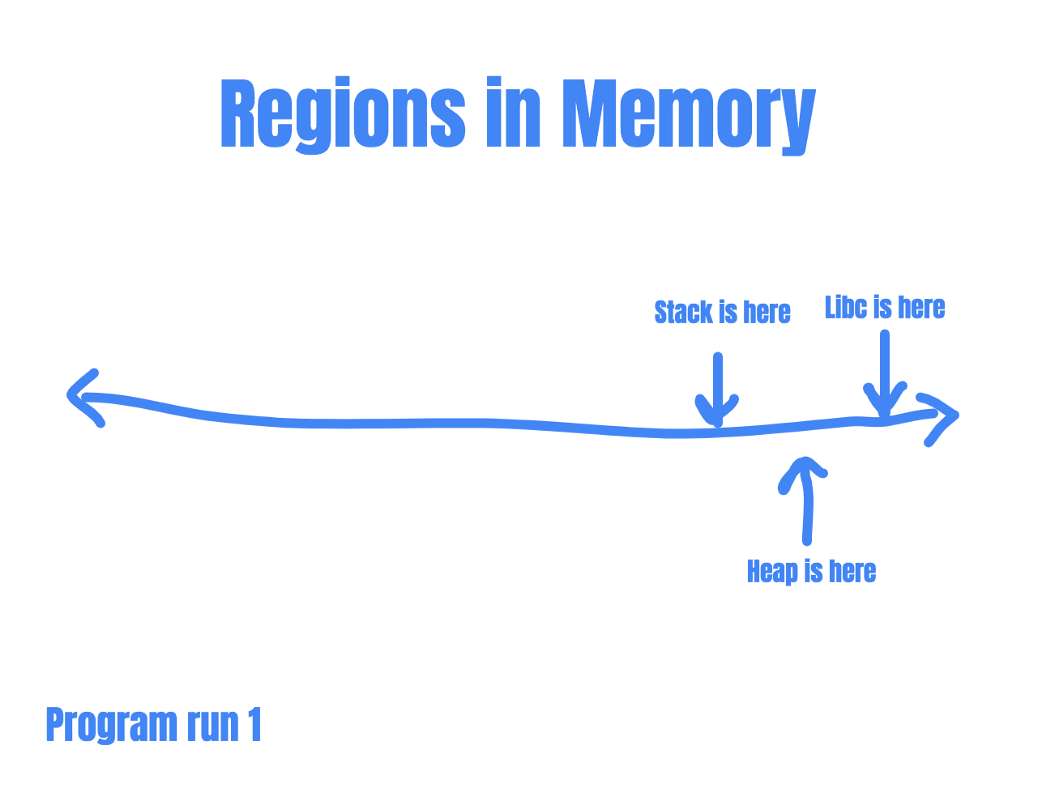

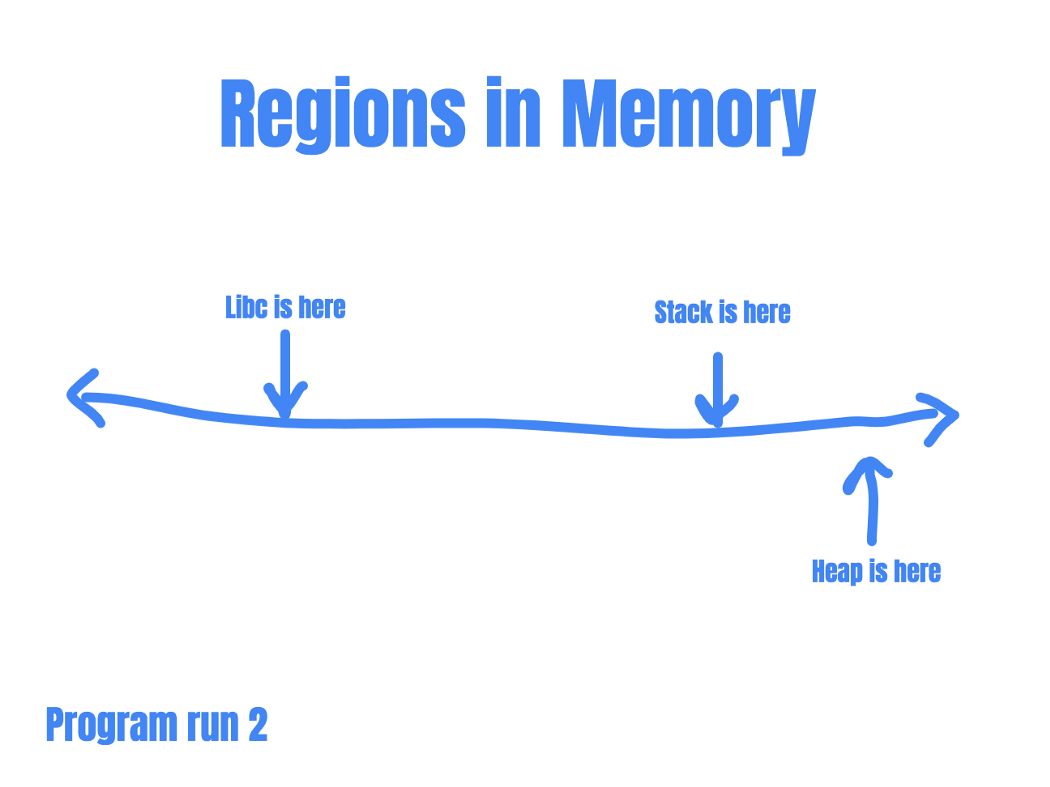

ASLR randomizes the address ranges for important memory segments such as the stack, the heap, program code and shared libraries such as libc. This means that memory segments are no longer static, and changes every time the program runs.

By randomizing the address layout between program runs, ASLR protects against attacks that rely on knowledge of where usable code is located, such as ROP and Ret2libc. Because even if a bug allows an attacker to control the program’s instruction pointer, the attacker would have no idea where to redirect the program flow.

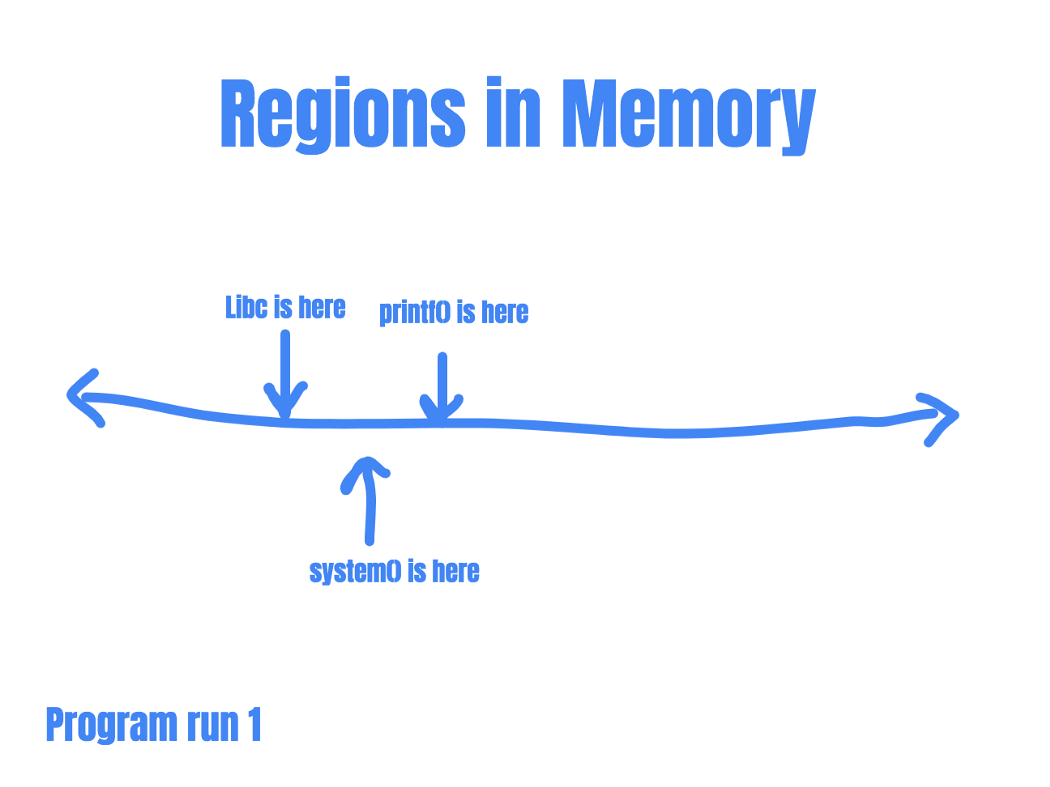

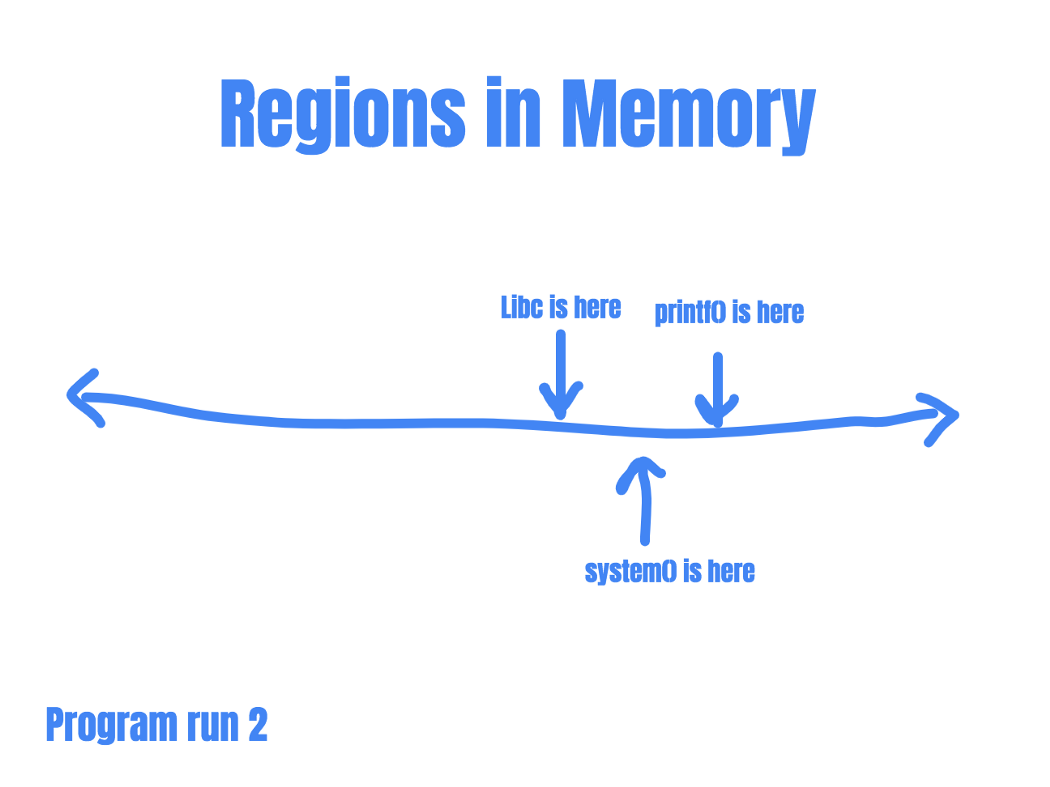

For example, let’s say as an attacker you are trying to launch a Ret2libc attack. To do that, you’ll need to know where the address for system() is.

So you run the program and was able to locate the address of system() within libc: 0xdeadbeef. You construct your exploit based on the assumption that system() is located at 0xdeadbeef, and rerun the program. If ASLR is enabled, your exploit would fail the next program run. This is because the location of libc has changed since the last time you run the program.

So, even if an attacker is able to redirect program flow, she’ll have no idea where to redirect to……

Protection Bypass: Redirect to non-randomized segments

Sometimes, not all segments in memory are randomized. If even a single executable code segment is not randomized across program runs, an attacker can utilize that segment to launch a ROP attack or use that segment to redirect to other functions.

ROP

It becomes more difficult for attackers to find ROP gadgets since the code that they can work with becomes restricted, but it is still possible to achieve a lot of things, including arbitrary code execution.

Return to PLT & GOT

One of the ways places that attackers can redirect program flow to another function is through the Procedural Linkage Table (PLT) or the Global Offset Table (GOT). The PLT and GOT are used to point to dynamically resolved functions (more on this in later posts). When these sections are loaded at a fixed address, hackers can utilize these sections to obtain the location of the desired functions.

Protection Bypass: Info leak

An attacker might also be able to build exploits by leaking the locations of important code in memory. If an attacker can leak the address of an important function (such as printf()), she can use that location to deduce the address of more useful functions (such as system()).

This is because even in ASLR, not every memory address would be randomized, and each segment of memory will still have a predictable internal format. In shared libraries, for example, only the base location of the memory segment would be randomized. The offset of a particular function from the base address remains constant.

So if an attacker can know where printf() is, she knows where system() is.

These memory address leaks can usually be achieved by leveraging another vulnerability, such as a buffer overread or a format string vulnerability.

Protection Bypass: Partial address overwrite

ASLR does not randomize the entire base address of a memory segment, usually just the higher bytes.

If an attacker finds a bug that allows her to overwrite the instruction pointer, she can overwrite the lower bytes of the instruction pointer to point to more exploitable functions in the same code segment.

Let’s say the current instruction pointer is pointing to 0xABCD1234. Since the randomized parts of the address (0xABCDXXXX) is already loaded into the pointer, the attacker can overwrite the lower bytes of the address to redirect program flow within the segment. And as mentioned above, each segment of memory will still have a predictable internal format. The attacker can use the current address to deduce the address of the desired function.

Protection Bypass: Bruteforce

As mentioned above, ASLR does not randomize the entire base address of a memory segment, usually just the higher bytes. So it might also be possible to simply brute force base addresses. However, this is usually a waste of time unless the ASLR implementation is weak and has low entropy.

Protection 3: Stack Canaries

Stack canaries are another way that programs protect against binary exploits. They are randomized values that change every time a program runs. When placed in strategic locations (after a buffer or before function returns), they can be used to detect corruption of the stack.

Detecting memory corruption using randomized values

Unlike the above mitigation techniques, stack canaries have the ability to detect attacks. Programs achieve this by checking canary values before a function returns, and stop execution if the canary value is incorrect.

Since it’s virtually impossible to guess a random 64-bit value, attackers would not be able to craft an exploit without knowing the canary value.

< --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- ->< --- --- --- - ->< --- --- --- - - - - - ->

Buffer for user input Canary Other data

Like in the above example, if an attacker is able to overflow the buffer, she would have to overwrite the canary in order to reach other program data. If the program uses a stack canary, it can check if the canary value is intact and detect any attempts to overwrite other program data.

Protection Bypass: Stack Canary Leaking

However, if an attacker can read the canary value during program execution, she can plant it in her payload and send it back to the program. For this to happen, the attacker would need an arbitrary or limited memory read, usually through a buffer overread or format string vulnerability.

Protection Bypass: Stack Canary Bruteforce

Since the canary is determined when the program starts execution, any child process of the program will usually have the same canary value.

This means that if the memory corruption bug can be used to overwrite canary values sent to the child processes, it becomes possible to brute-force the canary based on which child processes crash!

Using the above two techniques, attackers can acquire the canary value, place it into the payload and successfully redirect program flow or corrupt important program data.

Conclusion

These binary exploitation mitigations are becoming the default in modern programs. In order to successfully exploit a bug, attackers must not only understand the techniques used for memory corruption but must also have the ability to chain vulnerabilities together to bypass these mitigations.

Every additional layer of protection makes exploitation more difficult and adds security to the program. However, these mitigations do not make exploitation impossible. The most reliable way to prevent attacks is still to program safely and eliminate entry point vulnerabilities.

Thanks for reading! I realized that this post is dense and somewhat (very) theoretical, but in the future, we are going to dive into what it would look like to exploit and protect against these issues in the wild. Stay tuned!