Hacking Encryption With Signing Oracles

And why you should never reuse encryption keys!

I’m always looking for ways to find more IDORs.

Lately, I noticed a trend in the web applications I’ve been testing: protecting against IDORs by using encrypted parameters.

For example, sites would store user info under encrypted endpoints like this one:

example.com/user/AE38Bhha3d0pqqg3H/messages

Where AE38Bhha3d0pqqg3H is the user’s encrypted username. This approach can be secure. Because if attackers can’t predict a user’s encrypted username, they can’t access the private URLs.

Today, we are going to talk about why it is a bad idea to merely rely on obscured parameters, and what attackers can do to bypass this layer of security if no other protection is in place.

First off, what are oracles?

Perhaps you are familiar with oracles in the conventional sense. They are people who speak to gods in order to predict the future. But who, or what, are the oracles in cryptography? And how can they help us hack an application that uses encryption as a security mechanism?

Signing oracles

In web security, signing oracles are endpoints that can help an attacker predict encrypted values.

But why does this happen? To create unpredictable parameter values, applications sometimes use encryption that responds with the same output given a particular input (or simply map an input to a more complicated, unguessable output).

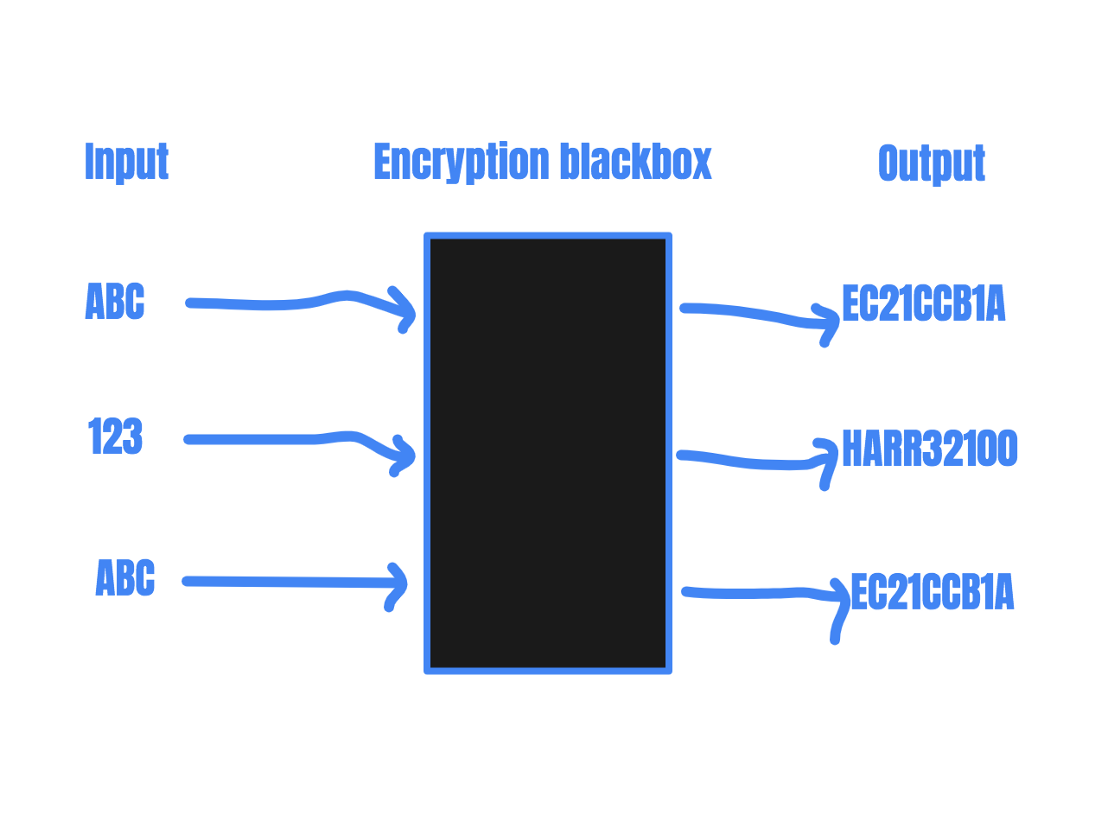

Every time that input is submitted, the function responds with the same output. For example, let’s say the encryption function described below is used to encrypt a user’s password file path as a defense against IDOR:

The encryption function will return the same value for each unique input.

This site, example.com, stores a user’s password at ”example.com/user/Encrypted_username/password”. User ABC’s password file is stored at ”example.com/user/EC21CCB1A/password” and user 123’s password file is stored at ”example.com/user/HARR32100/password”. So far, so good. Since attackers cannot predict the encrypted value of a user’s username, they cannot predict the URL that stores the user’s password. The password file is thus protected from outsider access by the obscured URLs.

Now, there are a lot of things that an attacker can do to potentially bypass this protection: she can try to reverse engineer the encryption algorithm or try to leak encryption keys used by the application. But let’s assume in this case, none of these options are possible.

Where it all goes wrong…

This approach is secure until the application gives the attacker a way to predict the encrypted values. Assuming that the encryption algorithm is secure and the encryption keys are not leaked anywhere in the application, are there any other ways for an attacker to do that?

This is where signing oracles come in. Signing oracles occur when the same signing method and encryption key are used in two places. This allows the attacker to predict the encrypted values that belong to other users by using another endpoint that allows her to control the input to the encryption function. She just needs to use the functionality to generate the random token instead of understanding and breaking the encryption function.

For example, let’s say there is functionality on example.com that allows users to query the public info of other users. This functionality is located at ”example.com/user_info?user=USERNAME”. This functionality will return a user’s age, role on the site, and the URL of their profile picture.

example.com/user_info?user=ABC

returns

{"username": "ABC", "role":"admin", "age":"21", "profile_pic":"example.com/uploads/profiles/EC21CCB1A"}

Note that the encrypted username used in the file path of the profile picture is the same as the one used to access a user’s password file. One can do the same and query the info of user 123.

example.com/user_info?user=123

returns

{"username": "123", "role":"member", "age":"27", "profile_pic":"example.com/uploads/profiles/HARR32100"}

Using this functionality, an attacker can now reliably predict the “unguessable” URL parameter by obtaining the encrypted usernames from the ”example.com/user_info” endpoint.

Accessing the password files

If the application employs no other security mechanism besides the encrypted URLs, attackers can now access anyone’s password file by first obtaining the encrypted password from the oracle endpoint, then accessing the password file using the learned encrypted value.

example.com/user_info?user=ABC

returns

{"username": "ABC", "role":"admin", "age":"21", "profile_pic":"example.com/uploads/profiles/EC21CCB1A"}

then access

example.com/user/EC21CCB1A/password

Preventing signing oracles

The fundamental cause of this vulnerability is that the application reuses encryption methods and keys, causing attackers to be able to deduce encrypted values given an arbitrary input.

Applications should prevent reusing the same method and encryption keys to sign information in different parts of the application. Developers should also prevent reusing encryption methods and keys across different applications that belong to the same organization.

Finally, security through obscurity is not a good idea in general. To prevent information leaks and IDORs from happening, it is best to use an additional layer of access control in addition to an obscured query parameter.