SSRF In The Wild

A totally unscientific analysis of those SSRFs found in the wild.

This is an analysis of publicly disclosed SSRF vulnerabilities. I will go into where these vulnerabilities were found, the criticality of these bugs, and the fixes implemented by the vendor after the report.

The study that you are about to read is totally unscientific, uncomprehensive and mostly just done for fun. I will use the terms like “roughly” and “about half” a lot, because most of the time, I just can’t be bothered to count. Read on if you will. You have been warned :)

Why I did this

A few months back, I decided that I wanted to learn more about the SSRF vulnerability class.

You know the feeling when you feel like you understand a concept, but still can’t fully grasp it? That was my relationship with SSRF. So I decided that the best way to get to know SSRF better is to go hunt for it in the wild, and actually capture one for myself.

And in order to hunt a new vulnerability class, I first have to gain more insight into how, why and where these vulnerabilities actually occur.

So I decided to gain this knowledge by reading every single publicly disclosed vulnerability report on Hackerone that is about an SSRF bug, in order to study:

- How are hackers finding SSRFs?

- Where do SSRFs occur?

- What did the application do wrong to cause the SSRF?

Getting started

My research project started with two simple Google searches to amass the raw reports for my analysis:

site:hackerone.com inurl:/reports/ "ssrf"

site:hackerone.com inurl:/reports/ "server-side request forgery"

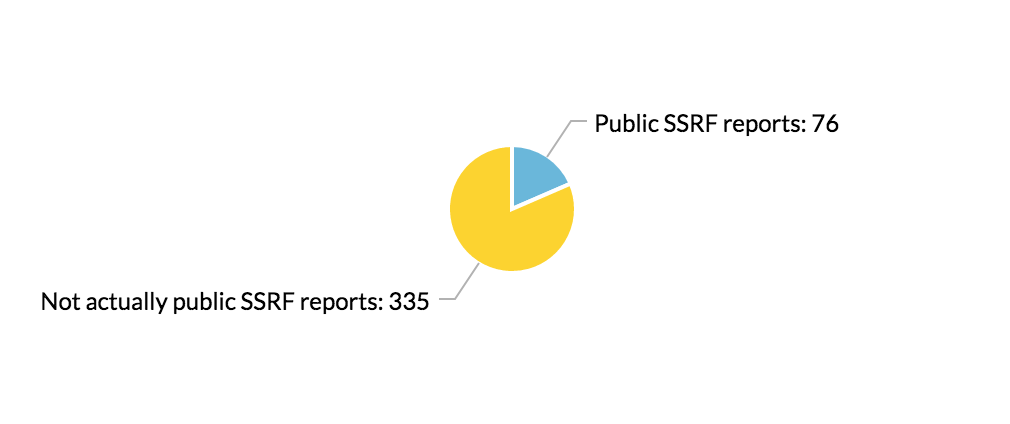

These two Google searches yielded 412 results at the time. Does that mean that there are 412 reports to read? Unfortunately not.

First of all, there is a large number of overlaps between the two Google search results. This is to be expected. The purpose of taking the union of the two result sets is to ensure the largest set of results to work from. Most reports that contain the term “server-side request forgery” also contained the term “SSRF”.

In addition, after filtering out the duplicate results, a large number of the resulting links point to either limited disclosure reports, reports that are unrelated to SSRF, or reports that are actually private. Here are the Google search results from the two search terms:

After filtering out all of the reports that would not be useful, I was left with a total of 76 publicly disclosed reports to go through. And now it’s time to read through these reports!

The research process

When reading these reports, I mainly looked at a few things:

- What feature did the SSRF occur in?

- Was there any SSRF protection in place before the report?

- How critical was the SSRF? What can be done using this particular SSRF?

- What was the fix implemented by the vendor after the report?

I read each report and categorized them according to the above criteria. I also looked at the fixes implemented by the vendors, and if any bypasses were found after the initial fix. In addition, I went to each of the sites that were found vulnerable and tried to find further bypasses myself. Here’s the actual state of my browser tabs for a week:

Results and analysis

Without further ado, here are the results I found from the publicly disclosed reports.

Vulnerable feature

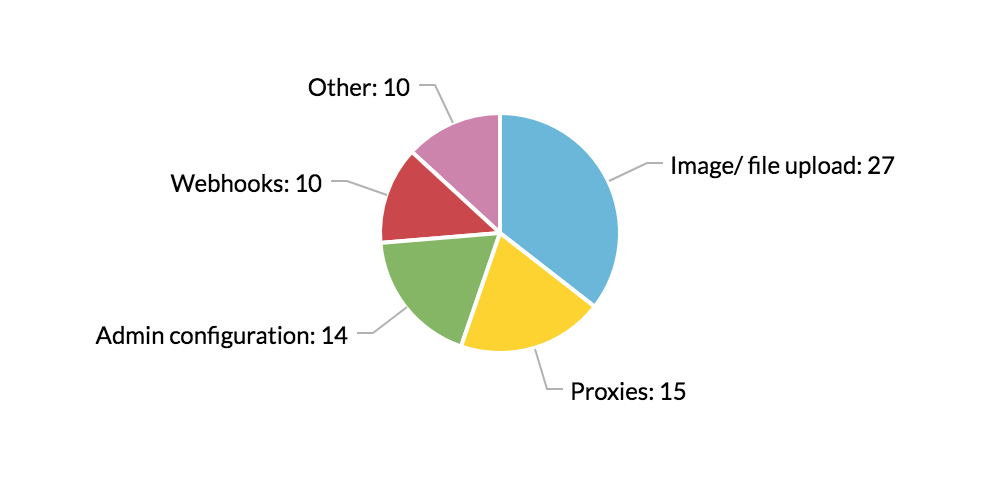

First, here is the breakdown of the 76 reports based on the feature that the SSRF occurred in.

The “Admin configuration” category mostly consists of SSRFs caused by XXEs when the site allows the importing of settings as an XML file. Whereas the “Other” category includes features that take in a URL that is not for file upload/ proxy/ webhook purposes.

As you can see, most SSRFs in these reports occur in file upload, proxy or webhook services. This is consistent with most documentation about SSRF vulnerabilities out there, and these features should be the first places you go to look for SSRF vulnerabilities.

Another interesting thing to note is the variety of file types that could be used to cause an SSRF. Any file that could contain a URL that would be parsed by the application can potentially trigger the vulnerability. Most of the files uploaded as POCs in these reports were SVGs, JPGs, XMLs and JSONs.

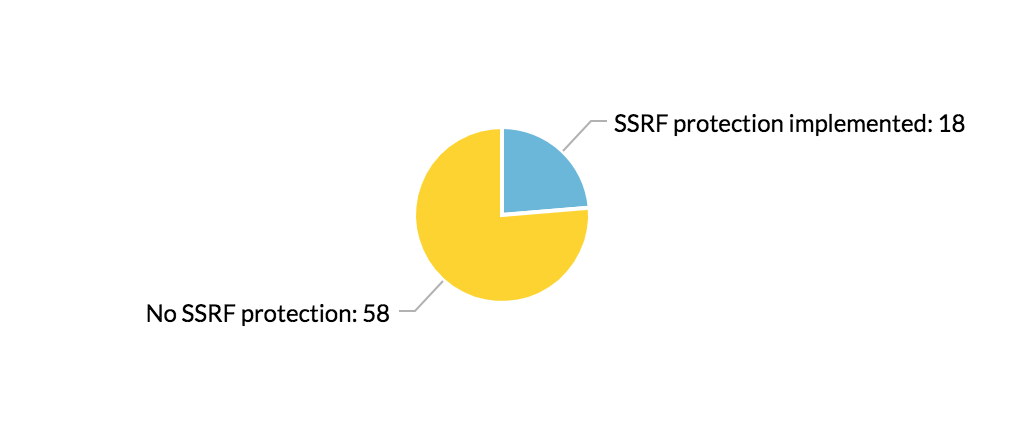

SSRF protection before the report

I then looked at the SSRF protection implemented before the report was submitted. Was the report about an SSRF protection bypass? Or was it on an endpoint with no SSRF protection at all?

Much to my surprise, most of these reports were about features that completely lack SSRF protection. And a lot of these reports were made to tech firms that usually handle security well, including Dropbox, Shopify, Slack, and Twitter.

I am guessing this is because of a lack of awareness of how and where SSRFs can manifest. For example, a lot of the disclosed vulnerabilities did not occur where the application accepts a URL from the user directly (the obvious SSRF suspects), but where the user uploads a file and the application parses that file. These types of SSRF vulnerabilities are less apparent and can sneak into many features.

Criticality of the SSRFs

Most of the SSRFs in the reports were classified either as a High or a Medium.

However, not many researchers in the reports attempted to escalate the bug. Most demonstrated the vulnerability by reaching known ports on the local machine. This is probably because the researchers are working within the bug bounty framework and do not want to step over the line, but I imagine there is a lot more that can be done using the bugs found.

Fix implemented by the vendor

Most reports, 46 of them to be exact, resulted in an implementation of a blacklist (or additional blacklists if protection was already in place). Two of the reports resulted in a complete disabling of the feature.

For the other reports, the vendor did not disclose what kind of protection was put in place as a result of the report. But most likely, some sort of blacklist or input sanitation was adopted to protect against future attacks.

Unexpected wins

During the process of studying these reports, I retested most of these sites and tried to bypass the protection implemented after the report. I retested around 25 of these endpoints. Using the SSRF bypass techniques that I have learned in the past, I was able to find a bypass to one of the reports due to an incomplete fix. This vulnerability was then reported to the vendor and fixed.

Here are some of the techniques that I used.

In addition, I also found a few other bugs (not SSRFs) on the sites that I retested, mostly CSRFs and info leak issues.

Lessons learned

Polish your SSRF-dar

When looking for SSRF vulnerabilities, file upload URLs, proxies and webhooks are good places to start. But also pay attention to the SSRF entry points that are less obvious: URLs embedded in files that are processed by the application, hidden API endpoints that accept URLs as input, and HTML tag injections.

Escalate, escalate, escalate!

Reading the disclosed reports, I was consistently surprised by the fact that most researchers did not try to escalate the vulnerability at all and instead, reported it immediately. Seems to me like there is a lot of unrealized potential. SSRFs are very versatile and can have severe consequences, who knows, they might be the key to your next RCE!

Read about a great bug chain that started with an SSRF here.

More public disclosure, please!

Though I was able to find many reports to read, a large portion of the disclosed reports I found was actually “limited disclosure”. This means that only the report title and a summary were made available. I found a lot of the report titles and summaries intriguing, but they often did not provide enough details for others to learn from it.

So the next time you find a vulnerability, fully disclose it! Or, if the vendor does not agree to full disclosure, strive to write a summary that will allow others to gain knowledge from your discovery. Your efforts will be much appreciated!

Conclusion

During this process, I had fun, and I found some bugs.

Coming out of my project, I feel like I now have a much deeper understanding of SSRF vulnerabilities as well as the intuition to actually go out and find some of them. Now, back to hacking!